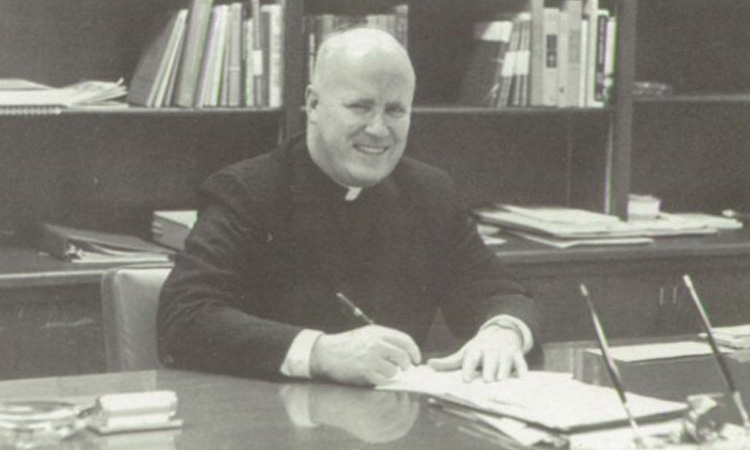

In Toledo, Ohio along the Maumee River, just a few miles inland of the western tip of Lake Erie, Jesuits have been in residence since 1868. By invitation of Bishop Amadeus Rappe of Cleveland, Jesuits from the Buffalo Mission began St. John Berchmans College in September 1898, led by Fr. Peter Scnitzler, S.J., on the corner of Walnut and Superior Streets. On May 22, 1900, the school would be incorporated under the name of St. John’s College and amended in 1903 to become St. John’s University, where it served the Toledo community until the Depression of the 1930s led to the closing of St. John’s in 1936.[1]

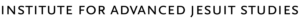

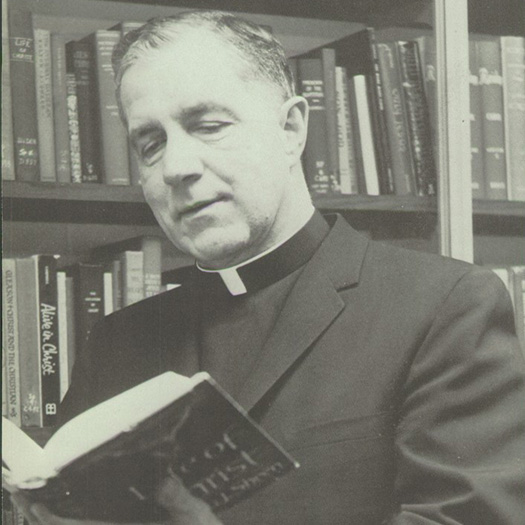

It was re-established by the Detroit Province in 1965 as a four-year college preparatory high school at its current location, led by Fr. Nicholas H. Gelin, S.J. as the first president and Fr. Robert J. McAuley, S.J. as the first principal, who later served as president for seven years.[2] Today, St. John’s Jesuit High School and Academy serves ### young men in grades six through twelve.

In order to understand Jesuit educational history, we must not only look to engage the big documents of Jesuit education such as the Ratio studiorum, Characteristics of Jesuit Education, or the Ignatian Pedagogy Paradigm, but we must do so in tandem with the engagement of the local histories—the ways in which Jesuit educational institutions have had to adapt such documents to the local contexts. What were the challenges and graces that have led to what St. John’s Jesuit is today and how does its history connect to the broader Jesuit educational heritage?

We interviewed Fr. Donald (Don) Vettese, S.J., former president of St. John’s and founder of the International Samaritan, a major global nonprofit that focuses on raising the standard of living in some of the world’s most poorest communities. During his tenure as president of St. John’s from 1992 to 2007, he served to improve the school’s campus and further its mission through initiatives and campaigns for endowments, renovations, scholarships, and the expansion to include the Academy, opening up the school for grades seven and eight.[3]

Landscape of the Early 1990s

Fr. Vettese recounted the trajectory of diminishing enrollment in the early 1990s and the shrinking population of the Rust Belt region of the American Midwest. Despite many of the buildings at St. John’s being in disrepair at the time, he notes that “the spirit of the school was strong there. There was a good history of Ignatian values being built into the curriculum.”

Fr. Vettese’s initial five-year plan included things such as improving the academics by hiring staff to improve the quality of education, building a good college counseling program, investing in infrastructure, and increasing the diversity of the student population. “One of the challenges was we didn’t have very many [economic or ethnic] minorities,” he recalls. Pointing to the mission of the school and the Gospel, Fr. Vettese discussed the importance of increasing the diversity of the school. He states, “When we go beyond middle and upper-middle class students and bring in lower class students, we are expanding the opportunities for everybody involved. We are helping them get different points of view right in the classroom.” This led Fr. Vettese to create the Toledo 20/20 Scholars Program, an initiative started to provide resources and support for economic and socially disadvantaged students who would otherwise be unable to attend the school.[4]

Full Participation in the Educational Environment

In his research, Fr. Vettese found that scholarship programs that helped fund students’ tuition still had high attrition rates. He recalls:

“What I learned was that one of the reasons there was attrition at St. John’s, as well as other schools in the region and perhaps the country, was that they weren’t being included. They weren’t able to participate in the full life of the school and the reason, in part, was many of the scholarships were just scholarships. They didn’t provide for what was sometimes called “extra-curricular.” I took exception to that word. This is not extra-curricular. It’s a central activity.”

Full participation in the educational environment included costs such as sports equipment, field trips, tutors, college tours, etc. The work of endowing the school’s activities, he suggests, must include endowment beyond just tuition money. It must aim to “pay for all that is required to participate fully in the life of the school.” Fr. Vettese points to the work of tending to the accessibility and centrality of these elements as factors in lowering the attrition rates in the school’s history.

The Jesuit tradition carries a long-standing heritage of placing attention to the learning and growth of activities outside of the traditional classroom. Joseph Maxwell, S.J., former president of the College of the Holy Cross 1939–45 and of president of Boston College 1951–58, wrote, “In our own educational tradition we find that extracurricular activities were nurtured and developed … Through them some students may possibly learn more things which receive active expression in their lives than do some of the things they acquire in the classroom.”[5] Such activities were also ways in which, the 1570 Constitutions of the Jesuit German College noted, “to keep the college happy” and “to keep the college healthy.”[6]

Funding for the Mission

When referring to the role a board serves for a Jesuit school, Fr. Vettese declared that the two major functions and responsibilities are to 1) “protect and promote the mission,” and 2) “as a fiduciary to fund the mission.”

Whether it was bringing students to share their stories or making an appeal to foundations backed by research, Fr. Vettese has a wealth of experience in fundraising for the mission, a trait that Jesuits and lay leaders in education don’t necessarily receive as part of their formation. He notes:

“I think people can be shy about asking for money. And if it helps, you’re not really asking for money. You’re asking for money for some thing for some person. In the cases I’ve talked about, it’s either poor kids and our schools or poor kids and poor people in the world. That’s what you’re doing. You’re helping those people. The money is, if you will, secondary. It’s important. But why are you asking for it?”

He continues:

“If you believe in your mission and you have a reason to believe a donor would be capable of helping and may be interested, go! Go ask! You know, if the Boy Scouts are coming out of the office right before you went in, okay! [The donor has] a decision to make. Sometimes they’ll give something to everybody.”

Funding for the mission has always been an important part of running schools, even back in Ignatius’s times. In 1549, St. Ignatius wrote a letter to the Jesuits leaving to found the Jesuit College of Ingolstadt. In it, he speaks of the importance of having good relations with the Duke of Bavaria, the need for the college as risen by the community, and the focus to have it be endowed so as to “be free of [the expenses] and the teachers’ salaries, to take steps for getting a perpetual endowment for the college.”[7]

The question of endowments traces back to the beginnings of the Society’s involvements in schools and was particularly important because students were admitted without cost.[8] In the First General Congregation of the Society of Jesus (1558), the Jesuits note in Decree 74 that “endowment may be allowed which, for the glory of God, the charity of benefactors is accustomed to provide for the upkeep of those who serve the common good of the colleges or who labor for that good in the study of letters.”[9] However, as the success of founding schools increased in the middle of the 16th century, the Society had to deal with the question of where to place their attention and resources, deciding to focus on those with endowments and that could bring potential vocations and teachers in the future.[10]

One of the monumental documents of Jesuit education in the past half century, Characteristics of Jesuit Education, which came out in 1986, not too long before Fr. Vettese’s tenure at St. John’s, alludes to the ways in which “Ignatius accepted schools only when they were completely endowed so that education could be available to everyone … Financial assistance to those in need and reduction of costs whenever possible are means toward making this possible.”[11] Fr. Vettese comments, “we did [endow schools] in part, by the way, but [Ignatius] was right in saying you’ve got to have sustainable funding for the future. You can’t serve people without it.”[12]

Board Education

However, being able to live out and operationalize the ‘preferential option for the poor’ in an institutional sense is a complex and difficult task.[13] For St. John’s, the proposal of the 20/20 Program, as with any large proposal, raised questions of the source of funding, its sustainability, and whether it was truly in line with the mission. It was a time when the school had to discern whether their mission was social and to the disadvantaged in addition to being a private college preparatory school, a discernment that many Jesuit schools underwent in the past half century.

In the 1960s, the cultural volatility of the times in addition to the movement towards a preferential option for the poor under the Jesuits’ election of their new leader, Pedro Arrupe, led many Jesuit schools to reevaluate their mission. Opinions among members of the Society of Jesus were divided with regard to the schools with some invigorated to incorporate changes in admissions and curriculum, while others believed that such changes were naive and would destroy years of institutional development. The case of Campion Jesuit High School of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, which closed in 1975, serves as a cautionary tale of destabilizing changes and the challenge of successfully implementing a preferential option for the poor while cultivating financial sustainability and a unified vision.[14]

The change for St. John’s through this discernment required adequate attention and planning. In addition to the funding elements, Fr. Vettese recalls the central work of providing a board with formational experiences, “to put flesh on the bones that [the Jesuits and the Catholic Church] put into their documents.” Becoming oriented and reoriented to the mission is a continual process that he believes we need more of. He notes:

“Any good school leader is going to have regular programs on board formation and board education. You don’t do it once and then stop. You don’t just do a board orientation for new members and then not develop that. We’re all growing, and I think leadership especially ought to be having continuous quality education that their president and board chair ought to be providing for them. They ought to expect it. They have a right to expect it, and the leadership has a responsibility to provide it. So, yes, you want to talk about Ignatian practicality? That’s what Ignatius did. Look at how he lived, what he did and what he accomplished.”

Through General Congregation 31 (1965–66) of the Society of Jesus, governing boards would officially become recommended to be established in Jesuit schools across the world, whose membership would include both Jesuits and lay people.[15] Documents of the Society of Jesus note that these boards were to take advantage of the professional competencies of its various members, who were to be “familiar with the purposes of a Jesuit school and with the vision of Ignatius on which these purposes are based.”[16]

Fr. Vettese continues, “Many board members will come to a not-for-profit board looking at the bottom line as a way of defining success. Well, I’d say that’s not Ignatian … Success would be in the service to the people you’re founded to serve.” In essence, Fr. Vettese calls us back to the need for renewal to promote, protect, and fund the mission, and the crucial element of continuous board formation programs towards this purpose.

Conclusion

St. John’s Jesuit High School & Academy continues to thrive today. Fr. Vettese notes, “They have two Jesuits working very hard there and a leader—a lay leader—who knows the mission, respects the mission, and is committed to promoting that mission. So, the fact that they don’t have a Jesuit running the place doesn’t diminish in this case, the Ignatian vision.” He continues, “Our alumni are a great testimony to where we’ve been and where we’re going.” With the declining number of Jesuits in the leadership and faculty at schools, the question of an institution’s Jesuit identity and alignment with the mission continues to be an important topic for reflection.

The work of funding for the educational mission that Fr. Vettese, and many other leaders in Jesuit education, continue to do is a difficult, but important process. While it has been noted in various ways in the Jesuit educational documents, it is a work that leaders like Fr. Vettese have tirelessly campaigned for to put “flesh on the bones” of such inspiring documents. Such work allows Jesuit schools, colleges, and universities to continue to form men and women for others throughout the ages and hopefully, the years to come.

Listen to the full interview here.

Recommended Jesuit sources:

- Ignatius of Loyola and Juan Alfonso de Polanco, “The Society’s Involvement in Studies (1551),” in Jesuit Pedagogy, 1540–1616: A Reader, edited by Cristiano Casalini and Claude Pavur, S.J. (Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2016), 55–60.

- Casey Beaumier, S.J., For Richer, For Poorer: Jesuit Secondary Education in America and the Challenge of Elitism.

- Jean-Yves Calvez, S.J., “The Preferential Option for the Poor: Where Does it Come From for Us?,” Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits 21, no. 2 (March 1989), 21–35.

Footnotes

[1] Gilbert J. Garraghan, S.J., The Jesuits of the Middle United States III (Chicago: Loyola University Press, 1984), 494–96.

[2] See John Francis Bannon, S.J., The Missouri Province S.J.: A Mini-History (St. Louis: The Missouri Province, 1977) and “News from the Field,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 28, no.2, October 1965, 133.

[3] Donald Vettese, S.J. (b. 1946) was born in Detroit, Michigan and entered the Society of Jesus on April 10, 1977. He was ordained a priest on June 19, 1982. Having earned three master’s degrees (University of Detroit, University of Michigan, and Jesuit School of Theology in Berkeley), he has been associated with Boys Hope as its national president from 1982 to 1992. His work in the area of Ohio led to a letter of commendation from President George H. W. Bush in 1989. See Vincent A. Lapomarda, The Jesuits in the United States: The Italian Heritage (Worcester, MA: The Jesuits of the Holy Cross College, Inc., 2004), 125–26.

[4] “The 20/20 Scholars Program offers opportunities to a variety of under-resourced and intellectual competent youth in the Northwest Ohio region. This not only gives them a chance to attend St. John’s Jesuit High School and Academy but also offers them a program with individualized care to assist the young men throughout their middle and high school careers. Although the program focuses on academics, it stresses the goal of growing these young men into future leaders by offering several tools and services to ensure that they thrive within the school community. They come to St. John’s Jesuit from a variety of schools and from very different backgrounds with one goal: they want to succeed.” Learn more about the 20/20 Program on their website.

[5] Joseph R.N. Maxwell, S.J., “Extracurricular Activities,” Jesuit Educational Quarterly 10, no.1, June 1947, 41.

[6] Giuseppe Cortesono, S.J., “Constitutions for the German College (1570)”, in Jesuit Pedagogy, 1540–1616: A Reader, edited by Cristiano Casalini and Claude Pavur, S.J. (Chestnut Hill, MA: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2016), 107–56.

[7] Ignatius of Loyola, Letters and Instructions (St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 2006), 297.

[8] In 1551, Ignatius had his secretary Jesuit Juan Alfonso de Polanco, write a letter to Antonio Araoz (1551–73), the provincial of Spain, about the best methods to found a college, based on his experiences in Italy. Polanco describes the asking a city, a ruler, a private individual, or a group of people to endow the educational endeavor. See Ignatius of Loyola and Juan Alfonso de Polanco, “The Society’s Involvement in Studies (1551),” in Jesuit Pedagogy, 55–60.

[9] General Congregation 1, Decree 74, in For Matters of Greater Moment: The First Thirty Jesuit General Congregations, edited by John W. Padberg, et al. (St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources, 1994), 87.

[10] General Congregation 2, Decree 8, in For Matters of Greater Moment. In General Congregation 2 (1565), the Society decided that serious consideration and moderation should be practiced when choosing which schools to continue operating. Decree 8 on this matter notes, “So far as possible they should be endowed and possessed of such an abundance of the necessities of life as to be able to sustain not only a number of staff but also that number of scholastics suitable for a seminary at the same college, so that from it sufficient staff might emerge to continue its work.”

[11] Society of Jesus, Characteristics of Jesuit Education (Rome: Society of Jesus, 1986), n. 86.

[12] It is important to note that while this charge of endowment was the ideal, not all of the Jesuit educational institutions in the early modern period were endowed. Many struggled to open and survive. See Kathleen M. Comerford, “The College in Florence: Opening, Funding, and Relationship to the Medici (1550s–1620s),” in Jesuit Foundations and Medici Power, 1532–1621 (Boston: Brill, 2017), 107–39.

[13] The push for a ‘preferential option for the poor’ within the Society of Jesus is often attributed to Pedro Arrupe, S.J., and his letter in 1968 titled, “On Poverty, Work, and Common Life.” In General Congregation 32 (1974–75) of the Society, Decree 4 had recommended a “solidarity” with the poor, with “families who are of modest means, who make up the majority of every country and who are often poor and oppressed.” Finally, in General Congregation 33 (1983), with the election of Fr. Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, S.J., as superior general, the ‘preferential option for the poor’ is explicitly named in Decree 1 which states, “The validity of our mission will also depend to a large extent on our solidarity with the poor. For though obedience sends us, it is poverty that makes us believable. So together with many other religious congregations, we wish to make our own the Church’s preferential option for the poor” (Decree 1, no. 48). See Jean-Yves Calves, S.J., “The Preferential Option for the Poor: Where Does It Come From for Us?,” Studies in the Spirituality of Jesuits 21, no. 2 (March 1989), 21–35.

[14] For an in-depth look at how this historically played out in Jesuit education in the 20th century, see Casey Beaumier, S.J., For Richer, For Poorer: Jesuit Secondary Education in America and the Challenge of Elitism.

[15] General Congregation 31, Decree 28, “On the Apostolate of Education”, in For Matters of Greater Moment, n. 27.

[16] Characteristics of Jesuit Education, n. 130.